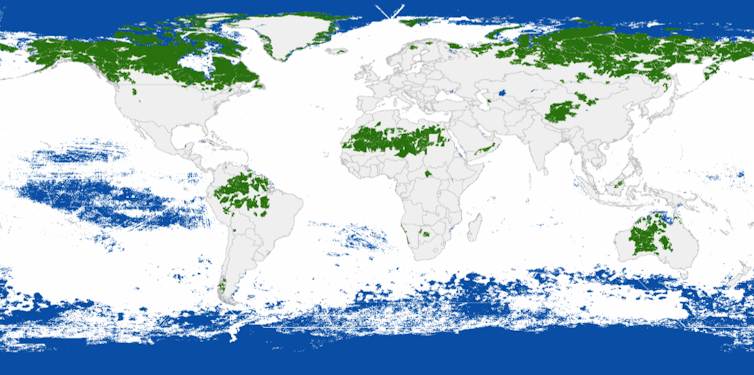

As planet earth becomes increasingly populated – and as rural areas become increasingly connected, the demand on the earth’s biologically productive areas, gets higher. Only about a quarter of the planet fits into that category since the rest are deserts, mountains, ice sheets, or land beneath infrastructure, which cannot be used for growing crops, fishing, grazing land, forests etc. That land amounts to 12 billion hectares, which has to be shared with other life forms who need wild spaces to be left untouched. Nonetheless, the calculations for global capacity per person (as of 2017) arrive at a capacity of 1.6 global hectares (gha) per person. In actual fact, to halt extinction, and with a growing number of human beings, it would be better to think in terms of 1 gha per person.

Seen in this light, the UK is overshooting – and badly so. In 2017, the average consumption per capita stood at 4.2 gha – more than twice the earth’s capacity. There are worse cases than this. The US stands at 8.1 per capita, and United Arab Emirates at 8.9. At the other end of the scale, still consuming at a sustainable level (at the current global population levels) are countries such as Nepal, Kenya, and India.

There are many factors that feed into the consumption of resources which has led to the loss of half the wilderness areas in the past 100 years, but transport is a big factor.

Car ownership

In many developing countries people do not travel long distances, for many reasons, but in a country like Nepal, the lack of road infrastructure is a big part of it. In Nepal’s case, the fact that it is very mountainous also impedes movement. In the Philippines, only 6% of the population in the Philippines own a car, and in in India, just over 2% of the population own a car. Compare that with the US, where 91% of the population have access to a vehicle.

A question of efficiency

Of course, the problem is that the car, while it may offer a comfortable, and independent form of travel, is a very inefficient use of energy. It is clearly much more energy efficient to walk or cycle than rely on a metal box weighing 2000kg to move you from A to B. Studies into energy burn for different transport options revealed that cycling consumes just 0.16 megajoules per km. The average car, on the other hand, burns through thirteen times that (2.1). When it came to public transport, trams came out one of the best at 0.91 per kilometre. This information should be front and centre for decision makers when it comes to looking at transport, and the ecological emergency.

The illusion of close

The other consequence of cars, is that by offering greater power possible than on foot, or even bike, more distance is travelled. Few would contemplate commuting 10 miles each day if they had to walk, in fact in pre industrial Britain, journeys that can now be done in a matter of hours, took days to complete. But the car has taken its toll on society – and weakened community. The village shop, especially in the age of the supermarket, is now mostly surplus to requirements. The car has made it possible to live almost anywhere. While the average mileage in the UK stands at around 4000, in the US, it’s more than double that. In the context of the car-centric world, it seems that the bigger the country, and the bigger mileage. Conceptually things change too. A weekend break that involves a 4-6 hour drive each way is considered no big deal. Such distances — and the resulting energy (and tyre) burn — goes some way to explaining why the US is living a five planet lifestyle.

Mining impact

The implications of car use go beyond just fuel burn and emissions. It’s also a question of the raw materials. Many car chassis are built using aluminium, which is extracted from a bauxite ore. One of the largest reserves of bauxite in the world are found in Guinea, West Africa. As mining companies seek to access the valuable raw materials, vast amounts of primary forest have been razed to the ground, replaced by roads, machinery and dust. The chimps found their habitat taken away, while local people struggled to grow crops under clouds of red dust and polluted water.

One planet living cannot contemplate this kind of ecocide. Understanding that the planet is a living planet, not just a resource pool, is crucial to protecting what remains of the earth’s forests, and ending environmental colonization. It is also a question that we as consumers, must think about.

Demand for concrete

The accompanying infrastructure required for cars, is also in direct conflict with one planet living. To cater to the UK’s 38 million cars, roads, bridges, car parks, petrol stations, garages, parking machines have all been expanded. The cement required for this infrastructure relies heavily on sand — the most consumed resource on the planet, besides water. But the rush to source sand is causing havoc in aquatic ecosystems:

“Dredging from river beds destroys the habitat of bottom-dwelling creatures and organisms. The churned-up sediment clouds the water, suffocating fish and blocking the sunlight that sustains underwater vegetation.”

Danger to wildlife

Making thing worse, is the loss of wild spaces for roads that slice through areas of wilderness. For the Iberian lynx, the biggest threat to survival is the car, although loss of habitat and pollution have also had an impact. Now just 400 lynx remain. The mountain lions of California face a similar fate, finding their habitat perilously latticed by huge 10 lane interstates. Stopping these animals from roaming freely has meant their gene pool has reduced dramatically. While the best thing for mountain lion would be for the roads to disappear altogether, at least there are now places afoot to create some bridges to help lions cross the roads safely.

Many more animals find their migration patterns interrupted by roads, and the resulting roadkill is a tragic reminder that the car comes at a high price to the natural world. In the UK, around 10,000 animals are reported as roadkill per year, although that is likely a fraction of the real number. Sadly the only badger or hedgehog many people will have ever seen has been one killed by a car.

What about electric cars?

Few of these problems will go away if we simply switch to electric cars. The question of mining, manufacture, infrastructure, if anything, will increase as we seek to make more cars — and their batteries from scratch. A single electric car uses up around 10kg of lithium, and 14kg of nickel. That’s a lot of minerals for one car, and once you start to scale up (estimates are for 500 million cars by 2050), that adds up to a lot of depleted ecosystems.

We have already had a preview of what human demand for technology can do. The rise of smartphones, tablets and laptops over the last few decades has resulted in vast swathes of Chile being plundered for lithium. Not only is this altering the landscape, but it’s siphoning off two thirds of fresh water supplies in Chile’s Salar de Atacama region.

Water use isn’t the only problem. Like any mining operation, the landscape is badly damaged, ecosystems are destroyed, and the surrounding area is often polluted. Farmers in Chile recall how flocks of flamingos used to inhabit the lagoons, which have now dried up. Meanwhile in Tibet local residents held protests in 2016 after their river was poisoned by a chemical spill by a Chinese mining company. Thousands of fish, yaks and cows all died as a result.

What next for transport?

The biodiversity impact on this demand for the earth’s resources has to be addressed if we are to hold onto a living planet. Freeing up the landscape of cars would be a huge step in the right direction, and has the potential to improve our well-being. We need to start exploring options such as cargo bikes, which overcome the problem of carrying things. Even e-cargo bikes would be considerably less damaging than cars.

More towns could also benefit from a tram network, and the UK could start to bring back bus routes which have dropped by more than 50% since the 1970s. There are ways to get out of the car, but it involves both behavioural change and structural change, and if the former fails, then the only way may be to put limits on the car.

Firstly we should stop cars from coming into town centres. Pedestrianizing centres makes room for cyclists and pedestrians to move around safely, and improves the wellbeing of those that live and work there. Secondly, parking prices should be immediately raised and rail prices dropped. Thirdly we should look to repurpose motorways and radically reduce speed limits. If motorways were repurposed as A or B roads, for bus (and initially lorry) use only, the leftover lanes could be returned to green area or made into cycle lanes. For the rest of Britain’s roads, lower speed limits could be imposed perhaps to a maximum of 30mph. This would make roads much less dangerous, give wildlife much more of a chance and reduce noise pollution. Imposing strictly enforced speed limits would also make the car a much less appealing as a mode of transport as it would lose much of its speed advantage.

Covid-19 crisis showed us that at extremely short notice, radical change was possible. People’s lives have been turned upside down for a lesser crisis than the collapse of our life support systems. One of the few silver linings has been the first lockdown which offered us a quieter, less polluted image of the world. People who are normally driven off the roads by cars, took to their bikes. There’s no reason why we cannot now make those radical changes. Rather than clinging to a stressful life of traffic jams, isolation, noise and air pollution, we can choose local and slow living. We might even be happier for it.

Fantastic. Cars kill amphibians, reptiles, otters, etc in this country working against nature conservation groups like the Wildlife Trusts. People drive incredibly short distances these days, through utter laziness and overvaluing their own time.