One year ago at Davos, the world’s most famous climate activist, Greta Thunberg, declared “our house is on fire”. She told the world’s rich and powerful that she wanted them to panic. The clip was widely shared, and her words have inspired signs at climate protests the world over. The phrase was also used as inspiration for a symbolic burning of a paper globe at a climate protest in Italy. “Our house is on fire” was an arresting way to begin the speech because it works to connect on three levels. The personal and emotive angle of defining the planet as our home; the urgency of escaping such a situation; and the all too literal consequence of planetary heating that is causing both burning and melting.

This powerful opening was swiftly followed up by evidence found in the IPCC’s report and the shared consensus that we have only years left to keep the warming below 1.5C. As far as media attention is concerned, Greta’s speeches have become famous for their evocative metaphors, and direct accusations of the world’s leaders. But this interweaving of climate science data has also been an essential part of her message and her credibility as an activist. She has tirelessly repeated the data about the remaining carbon budget and even chose to submit the report instead of presenting opening comments during a visit to the US congress in 2019.

Alarmist language?

Even though all of what Greta says is grounded in the best available climate science, some have branded her language alarmist. Extinction Rebellion have also been framed as extremists by the UK government for taking peaceful action to draw attention to the climate crisis.

During a television interview with an Extinction Rebellion spokesperson, Zion Lights, Andrew Neil accused the activist group of “scaring people” with their rhetoric and “apocalyptic predictions”. Rather than take the interview as an opportunity to discuss the climate emergency and its far reaching implications, for much of the interview Neil chose to focus on opinions at the more radical end of the scale The suggestion by Roger Hallam that there will be “slaughter, death, and starvation of 6 billion people this century” has been mostly discredited. But that doesn’t mean that there won’t be further suffering, loss of livelihood, displacement, or more loss of insect, animal and human life – all points raised by Lights during the interview. When challenged about Extinction Rebellion’s 2025 net zero ambition, Neil dismissed her answer as “picking one piece of research” to fit her agenda, despite calling on her to explain the “scientific basis” at the beginning of the interview. In doing so, he shut down another opportunity to speak in more detail about why delaying action is a dangerous gamble.

There’s no need for exaggeration – the truth is alarming

Neil’s attempt to skew the debate, is proof that the truth about the state of the planet and the future of the human race, may still be too uncomfortable to handle. Any suggestion that we are facing a threat to our survival, or a challenge to the status quo can be met with scorn – reminiscent of the flat earthers. But this will not, and cannot dissuade us from describing the climate emergency as just that, an emergency: a present and future threat.

Why we can no longer talk about climate change

The term “climate change” seemed to displace “global warming” as the term used to talk about the heating planet, but the term itself is problematic. The “change” has been used by some to try and justify the heating of the planet as a natural part of the earth’s cycle. Although this has been discredited, the term “climate change” does not reflect the urgency of the situation, and even “global warming” now falls short. We now have so much grim evidence of the effect of human activity on the the planet, that we no longer need rely on prophecy or hyperbole to convey the gravity of the situation. We just need to say it like it is. When species are going extinct at a rate of 200 a day and the world is hurtling its way towards at least 3 degree warming by the end of this century, it’s difficult not to sound alarming.

Has talk of a climate crisis achieved anything?

Last week Greta fired back at her critics in her opening remarks at Davos:

“don’t worry, I’ve been warned that telling people to panic about the climate crisis is a very dangerous thing to do. But don’t worry. It’s fine. Trust me, I’ve done this before and I can assure you it doesn’t lead to anything.”

And yet it has led to something. Maybe it hasn’t yet resulted in the kind of action necessary to halt emissions, but her powerful framing of climate change as an emergency, and as a crisis, has done a huge amount to raise awareness and has got some important results. The UK and EU both declared a climate emergency in 2019. Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders now frequently Tweets about the climate crisis, and at Davos Angela Merkel talked about the climate crisis in terms of “survival“. Greta’s words have also irked Trump and Putin.

While the recent UK may have been clouded by Brexit, climate has shot up the list in terms of voters priorities and the EU parliamentary elections saw a considerable uptick in Green candidates elected. That is an important first step in bringing about change.

Applying climate science to our lives

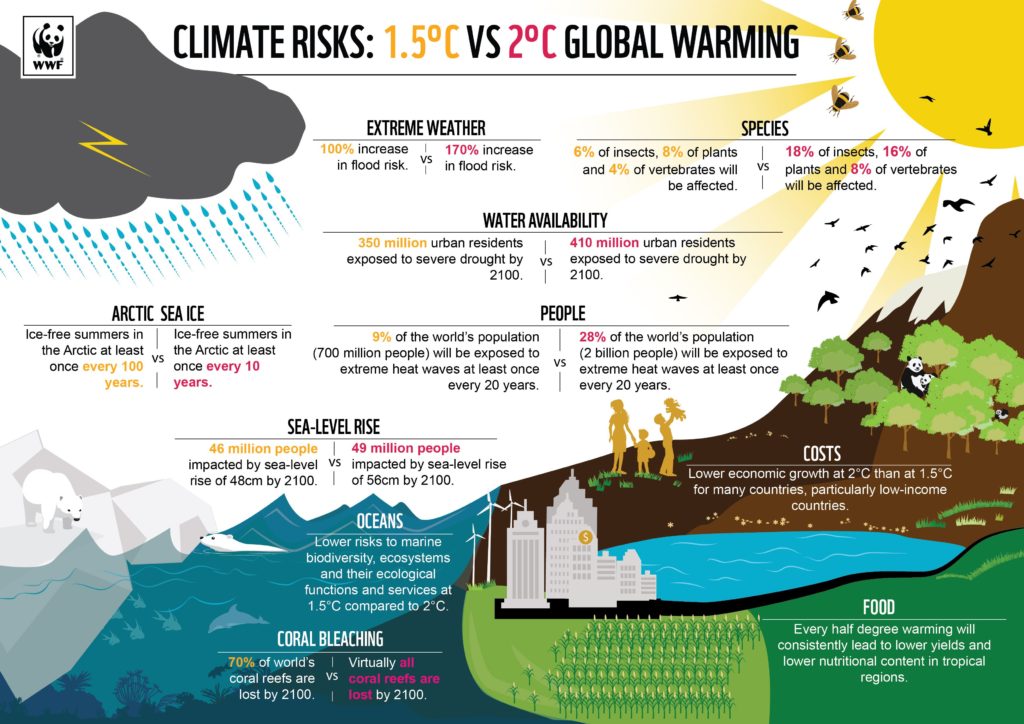

Greta has also managed to make data part of the conversation. By relentlessly citing the IPCC’s report, and mixing in key findings with her emotive speeches, Greta has used science – and the connotations of accuracy and reliability, to defy detractors. This also matters, as people need to know the facts. Many people still don’t know that we have less than 8 years left to stay below 1.5C – or what that actually means.

The first step has been making people aware of the crisis and what the future will look like if we continue on this path. The moral argument about the state of the living planet is being made, and is starting to register, but the battle now will be to translate the findings of climate science into what that means for our lives. Greta and Extinction Rebellion have done a lot to bring the crisis to people’s attention, but there’s still much more to do – we need to talk about specifics.

To get down to 2-3 tons of CO2 per capita (to halve emissions from their current global average) there will need to be some radical change. Those in the developed world need to know that the average Western citizen emits anywhere between 6 and 20 tons of CO2 a year – at best 50% more than the global average, and at worst almost 10 times that of an Indian citizen. We need to know what aspects of their lives are the most carbon intensive and that every ton emit counts, and every fraction of a centigrade counts. We need to know that every ton of carbon melts an estimated 3 square meters of sea ice.

The crisis we are facing must be explained in terms of our lives. Once people understand the facts, the climate emergency starts to make sense, and alarming though it is, once we start to take action- and demand change from our leaders, the future of the planet will start to look less frightening.

Further reading:

https://www.nature.com/immersive/d41586-019-02711-4/index.html

https://www.mcc-berlin.net/en/research/co2-budget.html

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/09/cut-emissions-flights-air-travel-flying